Last week I read and was extremely puzzled by

Tom Keneally's Gossip from the Forest.

Now I haven't read many of his books. At least part of the reason for this is that I saw the movie version of

The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith when I was really little and had nightmares for weeks about the evil treatment poor Jimmie received (because he was an Aborignine trying to fit into the white world) which made him go and kill lots of white people with an axe. To be accurate and not very PC, I was far more upset by the axe-murdering than the cheating of him out of his wages for however many yards of fencing it was. Poor Jimmie. This was probably the first time I'd ever come across a story about "the Olden Days" that showed our pioneering forefathers in a bad light. And it was a really scary movie!

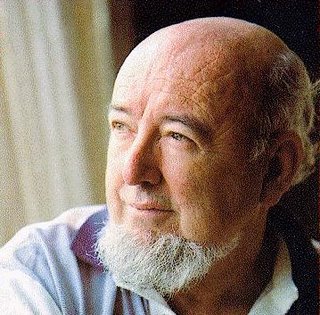

Another reason for not seeking out Keneally is because his twinkle-eyed face has been all over the telly and newspapers for the entirety of my life as "famous Australian author Tom Keneally". (And it is a nice uncle-ish face.) His every publication is extracted in the press and reviewed at length so that I feel like I've read it even though I probably haven't. I'm not even sure if I've read

Schindler's Ark but I really really disliked the sentimentality of Spielberg's movie. So even though he's part of the national cultural furniture and he writes accessible books on really unusual topics for an Australian writer, I haven't had much to do with him. The only exceptions I can think of are

Flying Hero Class about being in a plane when's it's highjacked and

Towards Asmara about the interminable Eritrean war for independence. Both of these was thoughtful, well-researched and well written.

Which brings me to

Gosip in the Forest: a phantasmagoric, absurdist bit of historical fiction about the men negotiating the armistice at the end of World War I. This is something we dealt with at school in five minutes: the Allies destroyed Germany with excessive reparations whcih led to economic troubles for a decade and created the ground for the rise of Hitler. This ignorance makes ask, do I believe it's all strictly true because Uncle Tom wouldn't lie to me? Or is it all made up?

The book is about a meeting between the French and English on one side and the Germans in a train in a French forest. At the beginning, the chief negotiator, the French Marshal Foch, desperately wants to make his name as a latter day Napoleon (except successful) by using the American armies, newly arrived in Europe, to invade Russia to put down Bolshevism. He doesn't want to compromise the onerous terms and is not at all interested in what happens to the German navy. The English want the navy destroyed.

The German envoys start off in Berlin where the soldiers have joined a socialist revolution. There is utter chaos and they have a Pynchon-esque journey where they're more worried about being shot by their own side than the enemy.

Basically, they're desperate for peace. The Allies refuse to believe in the level of chaos in Germany and won't compromise very much.

One of the weird things was some of the background to the lives of the negotiators. For instance, a German count who spends most of the novel drunk and raving claims at one point that his aristocratic mother only saw him for 10 minutes a day and, because his odd brother murdered his sister in the nursery and no-one believed this, he himself had to eat with a spoon till he went to boarding school (and faced various atrocities there). He then claimed that the German Kaiser had a similarly unloving childhood which made him not listen to commonsense.

Now I don't know what to make of this. Apart from not believing for a second that such a man even in extremis would make such a confession to an acquaintance, it sounds a bit like the way

Upstairs Downstairs explained the class system to viewers who hadn't lived through it. The book was written in the 1970s, a time remote from the events depicted with a great deal of cultural distance between the German aristocrats, so this sort of clunky explanation for German militarism could be needed to help the reader. But it seems discordant with so much of the book which was thoughtful and subtle and psychologically insightful. (There are some wonderful passages about how long it took to realise cavalry didn't work any more and about the tragedy of the millions of new widows and bridegroomless young women.)

What a longwinded way of saying "this book was kinda ok". If you don't believe me, please note that it has the mixed distinction of being shortlisted for the Booker prize.